- Home

- Michael Phillips

A Day to Pick Your Own Cotton Page 4

A Day to Pick Your Own Cotton Read online

Page 4

“I want you to have it, Mayme,” Katie repeated. “It will make me happy for you to write in it.”

“Thank you, Miss Katie,” I said, smiling and trying to keep from crying. “You’re too nice to me.”

“You’ll need a pen too,” said Katie, turning and looking over the desk. “Here’s one … and a bottle of ink.”

“I’ve never used a pen like that before,” I said.

“I’ll show you,” she said. “It’s a little hard to get used to. Practice on another piece of paper first before you write anything in your journal.”

She made me sit down, then showed me how to hold the pen and how to dip it in the ink. I made a mess at first, spilling a big splotch of black over the paper.

Katie and I laughed. But she kept showing me and I moved it around on the paper, pretending to make some words. And slowly I got the hang of it.

That night I sat down at the desk in the room I was using and opened to the first page of my new journal. I sat there a long time thinking what I should say. Finally I dipped the pen into the jar of ink and started writing.

This is what I wrote.

My name is Mary Ann Jukes. People call me Mayme. Im fiften yeers old an I grew up as a slave on a plantashun. But to munths ago all my fambly was killd by some bad men ridn on horses wif guns. I hid an then ran away an came to anoder plantashun calld roswood. I been here about to munths. I met a white girl calld Katie Klarborn. She let me stay an were friens now. I been tryin to read the Bible cuz wen we went back to where I lived before we foun my mamas an grandmamas Bible an Katies been helpin me lern to read. I also ben tryin to pray an Gods ben answerin some to an that makes me know hes takin care of us. Anoder black girl came here to whos in trouble. We helpt her have her baby an theyr stayin wif us. Katie an mes tryin to preten to run the plantashun so nobodyll know were jus three girls an a baby all alone here.

I set down the pen and looked at what I’d written. It wasn’t a whole lot better than what I’d written when I was younger. But it was a good start. And right then and there I said to myself that I’d keep writing, and would make this book Katie’d given me the story of my life, whatever came of it.

PUTTING OUR PLAN TO WORK

8

AFTER A WEEK OF KEEPING FIRES GOING ALL THE time in the main house and in one of the slave cabins, Katie said to me, “This is too much work. We’re going to run out of wood and kindling and matches. Why do we have to keep doing this and putting clothes out on the line if nobody’s watching?”

“ ’Cause we don’t know when somebody might be,” I said.

“Why don’t we just get it ready, then, and do it when we need to?”

“Because by the time they come, it’d be too late. We couldn’t do it after they were already here.”

Then suddenly it dawned on me that we had a big problem—what if anyone caught sight of Emma and William in the main house? Then we’d be in a fix for sure! The crazy way Emma carried on, no one would ever believe her for a house slave.

“Miss Katie,” I said, “what are we gonna do about Emma if someone comes?”

“Why can’t she just hide in the house?” said Katie.

“What if William starts fussing or crying? Or what if Emma gets scared and starts yelling and babbling like she sometimes does and we can’t shut her up?”

Katie thought a minute.

“I don’t know, Mayme,” she said finally. “But you’re right—we’ll have to do something with her if anyone comes.”

Our talk put an idea into my head a little while later. We could set a fire all ready to go in one of the slave cabins and maybe in the blacksmith’s shop. Then if anyone came, I’d run down and light it and then come back pretending to be coming from the colored village. If and when Emma got her strength back, she’d be a big help too.

“And we can do the same with a basket of laundry,” said Katie. “And let’s hitch up a horse and buggy outside so it’ll look like my mama’s fixing to go someplace.”

For the next several days we thought of more things like that, making plans and practicing what we would do the next time we had a visitor. We planned and practiced other stuff too, thinking of what we would do when somebody came, how we’d explain ourselves.

“But, Mayme,” said Katie after a while, “we’re going to wear ourselves out.”

“Emma will be able to help us directly,” I said.

“Not very directly. She’s still so scrawny and weak and needs all her energy just to keep William alive with her mother’s milk.”

“I reckon you’re right,” I said. “She ain’t likely gonna be much help till we manage to get some meat on her bones, and who knows how long she’ll be here anyway with those men she says are after her.”

It was a good thing that we’d come up with a few plans, though we still didn’t know what we’d do with Emma and William.

One morning I was coming back from the barn and heard a bee buzzing around up in the rafters. Probably a bee’s nest, I thought, looking up wondering where it was. Then the words came back into my mind from the old poem I used to hear the men singing. Pretty soon I was singing it myself as I walked toward the house.

“De ole bee make de honeycomb,

De young bee make de honey,

De niggers make de cotton en’ co’n,

En’ de w’ite folks gits de money.”

I smiled to myself. I sure wasn’t making any cotton or corn, and Katie wasn’t getting any money!

“De raccoon totes a bushy tail,

De ’possum totes no ha’r,

Mr. Rabbit, he comes skippin’ by,

He ain’t got none ter spar’.”

But I didn’t have time for any more of the verses.

Because just like we knew would happen, all of a sudden I heard a sound. I looked behind me and saw a covered wagon with painted writing on the side coming slowly, rattling along the road from the direction of town.

Two people were sitting in front. The minute I saw them I forgot all about bees and cotton. I ran straight for the house.

“Who’s that?” I said as I ran inside, then turned and looked out the window. Katie ran to my side.

“It’s the ice delivery man, I think,” she said, squinting to look.

“Will he come to the back door?”

“I think so.”

“There’s no time for me to get there going out the back,” I said. “I’ll run out the front where he can’t see me and go light the fire down at the cabin. You do like we planned and pretend your mama’s upstairs!”

“But, Mayme, what about Emma?”

“Put her somewhere out of sight and tell her to be quiet!”

I turned away and dashed through the parlor.

I was out of the house from the front, a direction where nobody could see me, while inside Katie hurriedly hid Emma and then ran upstairs herself. Then she waited for the man in his wagon to pull up and walk to the kitchen door while the boy who must have been his helper sat in the wagon. She had already opened a window looking right down over the kitchen door. When he got near enough, and trying to make her voice a little deeper like her mother’s, she called out loud enough so he could hear.

“Katie, Mr. Davenport’s here with the ice,” she said in the pretend voice. “Will you go down and tell him we need four blocks.”

“Yes, ma’am,” said Katie, changing her voice back to normal.

Then she ran down the stairs, through the house, and opened the door.

“Hello, Mr. Davenport,” she said.

“Good morning, Kathleen. I’m sorry I wasn’t able to make it last month. I take it you need some ice?”

“Yes, sir. Four blocks please. You can put it in the ice cellar.”

He walked back to where he had parked the wagon next to the ice cellar.

By then I was just getting to the slave cabins. I hurried inside the one we’d got ready and lit the fire we’d set. It only took a few seconds for the smoke to start drifting up throu

gh the chimney. I watched and waited about five minutes till the man and his boy had finished unloading the ice and taken them down the steps. When the man was walking back to the house, then I walked that way too. He and Katie were just starting to talk again when I came up. Katie looked toward me.

“Oh, there you are, Mayme,” said Katie. “Mama wants to see you. She’s upstairs in the sewing room.”

“Yes’m, Miz Kathleen,” I said, keeping my head down as I walked into the house.

“How much is the bill for the ice, Mr. Davenport?” asked Katie.

“Sixty cents for the four chunks.”

“I’ll go ask mama about it.”

Katie went inside, ran up the stairs, exchanged a look with me, got a few coins, and went back downstairs.

“Here is half of it. Mama wants me to ask if we can pay you the rest when you come next month.”

“Tell her that will be fine.”

“Thank you, Mr. Davenport.”

The ice man took the money, kind of looked about, saw the smoke coming from the fire I’d just lit, seemed to hesitate a second or two, then started walking back toward his wagon.

“Uh, Mr. Davenport,” said Katie. “I just remembered. Do you know who might be able to fix our windows … who my mama might be able to get to fix them for us?” she added.

He paused, turned, and looked back. “Why, Mr. Krebs, the glazier—your mama knows that,” he said.

“Uh, yes … could you wait just a minute please?”

Katie ran back inside. Mr. Davenport likely thought he heard voices talking from the open upstairs window. A minute later Katie returned.

“Could you please tell Mr. Krebs that my mama would like him to come out and fix these four windows that got broken?”

“All right … yes, all right, Miss Clairborne—I’ll talk to him. But—”

“Thank you, Mr. Davenport,” said Katie, then turned, went back inside, and closed the door.

By then I was nearly laughing to split my sides. Katie was some actress!

I had been peeking out of one of the windows from behind a curtain. I watched as the man just stood there a few seconds watching Katie come back inside, then kinda shook his head with a puzzled expression, and finally went back to his wagon, got up, shouted to his horses, then rattled off toward the Thurston place.

As soon as he was gone, I came running down the stairs laughing.

“You did it, Miss Katie,” I said. “You really made him believe your mama was right up there all the time!”

A sheepish smile crept over her face. Then she started laughing too.

We talked for a minute, then suddenly a startled look came over Katie’s face.

“Oh, oh—I forgot about Emma!” she exclaimed.

I’d forgotten too. “Where is she?” I said.

But already Katie had turned and was running into the parlor. She threw up the carpet and opened the trapdoor in the floor leading down into the cellar. The instant she did, the sound of a baby crying came up from the blackness below.

“You can come up now, Emma,” said Katie, taking two or three steps down the ladder. “Here, hand William up to me.”

“Miz Katie,” I heard Emma calling from below, “it was so dark down dere, I wuz skeered.”

“I’m sorry, Emma. It all happened so fast. But next time we’ll put a candle or lantern down there for you.”

“You gwine make me go down dere agin, Miz Katie?” wailed Emma as she climbed up out of the dark hole.

“Only if we have to, Emma. Only if someone comes again. But it will be better next time, I promise.”

A TALK ABOUT GOD

9

ONE DAY AFTER WE HAD JUST FINISHED THE milking, we were taking the cows out to pasture. As the two of us were walking along the road I glanced back. There were the eight or ten milk cows following lazily along, stretching out behind us in ones and twos. And I realized that we were doing it, we were getting up every morning and keeping things going. It might not have been much of a plantation, but at least the animals were still alive and we were surviving, although we were sure drinking a lot of milk. It was good for Emma, though. She was starting to fill out a little and was looking a mite less scrawny. And in time I reckoned William would start drinking some cow’s milk directly from a bottle instead of his mama’s breast.

I glanced back again.

The cows behind us didn’t care how old we were. They just went where we led them and ate the food we gave them and let us milk them. They didn’t care if we were black or white or young or old.

A wave of happiness surged through me as we walked. I ain’t sure quite what caused it. But with the sun shining and the cows clomping along and me and Katie just going about the day like it wasn’t so unusual and like we actually knew what we were doing, it was just a good feeling.

I snuck a glance over at Katie beside me. She had a contented, almost happy, carefree look on her face too. She had already changed so much from when I’d first come. I could see it in her expression, just in the way she walked and talked. She was so much more confident already. She didn’t look like a frightened little girl anymore. I think taking care of Emma had matured her more than anything. It made her feel useful and needed. She knew how much Emma and William depended on her for their very survival and that couldn’t help but make a body feel more grown up about things.

“Miss Katie,” I said as we walked along, “do you ever wonder why God let all this happen—our families getting killed I mean?”

“Do you think He let it happen, Mayme?” she said.

“I thought He made everything happen,” I said. “I thought that’s what God’s will was, everything that happened.”

“I don’t see how something as bad as that could be God’s will,” she said.

I thought about what she’d said a minute.

“I see what you mean. I guess I don’t see how it could be either, if He’s a good God,” I said. “But I thought everything was His will.”

“I don’t know,” said Katie. “My mama and daddy didn’t teach me too much about God.”

We walked along a while more. My mind was turning the thing around and around.

“Do you think He is a good God, Miss Katie?” I said after a bit.

“I don’t know. I just thought He was … God.”

“But what’s He like?”

“I don’t know. But doesn’t it seem like He’d have to be good?”

“Why’s that?”

“Well, if He’s God, He’d have to be good, wouldn’t He?”

“I don’t know. I don’t reckon I ever thought about it much before.”

“What else could He be?”

“Why do you think that?”

“I don’t know. It just seems that way. I mean, life is a good thing, isn’t it? So if God made it, He’d have to be good.”

“Life ain’t so good if you’re a slave,” I said. “And life ain’t been so good to you and me and Emma. How can life be good when there’s so much killing?”

Katie thought about that a minute.

“Maybe God made things good at first,” she said. “I bet there weren’t any slaves back then.”

“I reckon you’re right,” I said. “It sure don’t seem like God could want one person owning another and being mean to them and with folks of all colors being able to kill each other.”

“So if God doesn’t like people being slaves,” said Katie, “maybe He’s still good, even though people do bad things, like those men who killed our families.”

Again I thought for a minute. It was hard to get my brain to grab hold of the idea all the way. The harder I thought about it, the more it moved around, like the idea was trying to squirt out of my hand.

“But it still seems like He’d have done something to not let it happen, if He’s good like you say,” I said finally. “Why wouldn’t God make good things happen instead of bad things?”

“Maybe He can’t,” said Katie.

“W

hy couldn’t He? If He’s God, can’t He do anything?”

“I don’t know. Maybe He can’t make people be good if they don’t want to.”

“Hmm … I suppose that could be.”

“Maybe He doesn’t want to make all the bad things in the world go away, things like your being a slave, and those marauder men.”

“I wonder why not.”

“I don’t know,” said Katie. “But I see what you mean—why can so much bad happen if God is good? It seems like He ought to do something to keep it from happening.”

“Yet as much bad as has happened to us,” I said, “God’s taken care of us too. I think He cares about us, don’t you, Miss Katie?”

“Yes, I think He does.”

“So maybe there’s good and bad all mixed together, like it’s been for us. Even though terrible things have happened, God still loves us—at least we’re pretty sure He does. So that part of Him must be good. Though I admit, it’s still a mite confusing.”

We walked for a couple minutes just thinking.

“I wonder how you find out,” I said finally.

“Find out what?” asked Katie.

“What God’s like.”

“Isn’t that what the Bible’s for?”

“I don’t know, I just thought it was stories about olden times.”

“I suppose you could ask Him what He’s like.”

“You mean ask God?” I said. “Like we did before, when we asked for His help?”

Katie nodded.

“But how would He tell you the answer?”

“I don’t know,” said Katie.

“Maybe by how you feel,” I said, “like when I thought He was telling me to stay here. It was a mighty strange but good feeling to think that God was talking to me.”

We were just about to the field by now. We led the cows through the open gate, then closed it behind them. They frolicked for a few seconds in the thick, tall green grass, if something as big and clumsy as a cow can frolic. Then they got down to their business of the day, which was to eat as much of it as they could.

We turned and walked back toward the house. Neither of us said anything more for four or five minutes. We were about halfway back by then. I’d been thinking the whole way about what Katie had said a little while ago about asking God.

The Treasure of the Celtic Triangle- Wales

The Treasure of the Celtic Triangle- Wales From Across the Ancient Waters- Wales

From Across the Ancient Waters- Wales Hell & Beyond

Hell & Beyond The Braxtons of Miracle Springs

The Braxtons of Miracle Springs Angel Harp: A Novel

Angel Harp: A Novel The Russians Collection

The Russians Collection Treasure of the Celtic Triangle

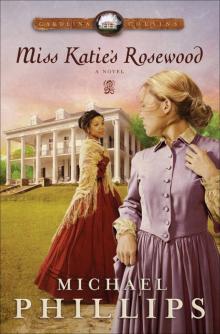

Treasure of the Celtic Triangle Miss Katie's Rosewood

Miss Katie's Rosewood Into the Long Dark Night

Into the Long Dark Night A Perilous Proposal

A Perilous Proposal A Place in the Sun

A Place in the Sun A New Dawn Over Devon

A New Dawn Over Devon Shadows over Stonewycke

Shadows over Stonewycke The Color of Your Skin Ain't the Color of Your Heart

The Color of Your Skin Ain't the Color of Your Heart A Home for the Heart

A Home for the Heart A New Beginning

A New Beginning The Soldier's Lady

The Soldier's Lady On the Trail of the Truth

On the Trail of the Truth Robbie Taggart

Robbie Taggart Land of the Brave and the Free

Land of the Brave and the Free The Inheritance

The Inheritance The Treasure of Stonewycke

The Treasure of Stonewycke Sea to Shining Sea

Sea to Shining Sea Stranger at Stonewycke

Stranger at Stonewycke Grayfox

Grayfox My Father's World

My Father's World Wayward Winds

Wayward Winds Daughter of Grace

Daughter of Grace Wild Grows the Heather in Devon

Wild Grows the Heather in Devon A Day to Pick Your Own Cotton

A Day to Pick Your Own Cotton Together is All We Need

Together is All We Need The Cottage

The Cottage Legend of the Celtic Stone

Legend of the Celtic Stone Never Too Late

Never Too Late Jamie MacLeod

Jamie MacLeod American Dreams Trilogy

American Dreams Trilogy Heather Song

Heather Song From Across the Ancient Waters

From Across the Ancient Waters Land of the Brave and the Free (Journals of Corrie Belle Hollister Book 7)

Land of the Brave and the Free (Journals of Corrie Belle Hollister Book 7) An Ancient Strife

An Ancient Strife Heathersleigh Homecoming

Heathersleigh Homecoming